The Three Aspects of Prostate Cancer Decision Making…Do You Know Them As They Apply To You?

Medical insight, personal stories and humor from a urologist who has been where you are now.

Why knowing “Who you are” in the context of your prostate cancer diagnosis is important.-

From “The Decision” Available on Amazon.com

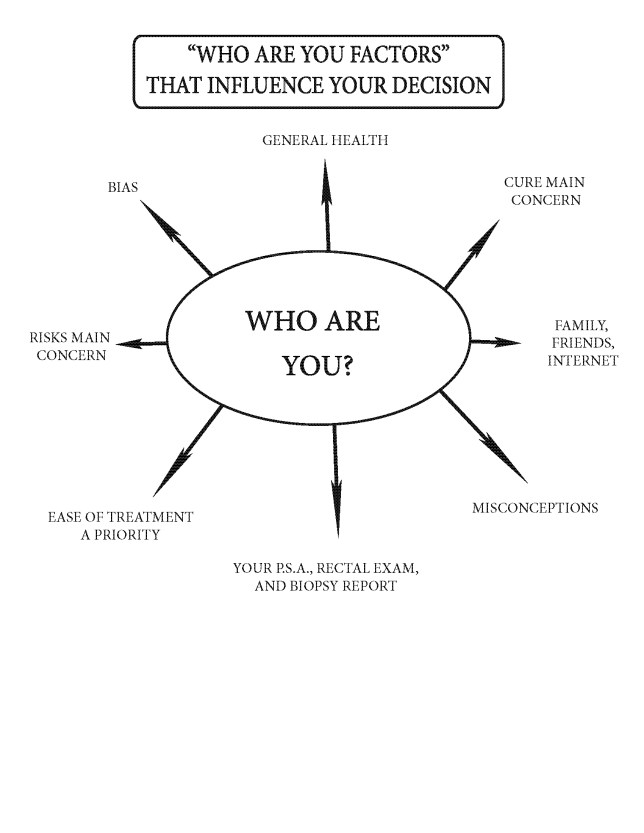

The decision of what treatment to choose is driven by several factors. It should be a decision that is tailored to you: “customized care,” as I like to call it. A common question to the urologist is, “What would you do if you were me?” A better question would be, “Who am I, what is important to me, and what is best for me?” The answers to these questions will vary from person to person and, in turn, will influence their decisions. These personal differences often explain why two seemingly similar patients will choose widely different courses of treatment.

What follows is a breakdown of the important issues that will influence your decision; your job is to examine each in the context of your particular situation. This self-evaluation will aid you in understanding the factors that will ultimately drive your decision. To do this, it is important to know the factors that distinguish you as a patient (your “who are you” factors), your underlying voiding pattern and potency level, and how each treatment will affect each. As a urologist, I commonly see the voiding side effects of the treatments, and for that reason, a particular emphasis on this aspect of the decision is discussed. Every patient with prostate cancer who receives therapy will have some voiding side effects. Because all of the treatments will affect how you void differently, an emphasis the on mechanics of male voiding and how it is impacted by the various treatments is discussed in detail. It is imperative that you understand the different issues regarding how you void. This is delineated in the risk-driven section.

What follows is a breakdown of the important issues that will influence your decision; your job is to examine each in the context of your particular situation. This self-evaluation will aid you in understanding the factors that will ultimately drive your decision. To do this, it is important to know the factors that distinguish you as a patient (your “who are you” factors), your underlying voiding pattern and potency level, and how each treatment will affect each. As a urologist, I commonly see the voiding side effects of the treatments, and for that reason, a particular emphasis on this aspect of the decision is discussed. Every patient with prostate cancer who receives therapy will have some voiding side effects. Because all of the treatments will affect how you void differently, an emphasis the on mechanics of male voiding and how it is impacted by the various treatments is discussed in detail. It is imperative that you understand the different issues regarding how you void. This is delineated in the risk-driven section.

“Who are you?” factors

Each of these categories should be evaluated in the context of your particular situation and then used together to make your decision. The relative importance each will play in your decision-making process will be determined by you and will be unique to you. With time, you will combine these “who are you” factors with all of the information about your cancer and your assessment of risk versus cure to arrive at the decision that is best for you.

General health, age, and years at risk-If you are young and healthy think aggressive treatments, if you are older with other medical issues think less aggressive and overly value ease of treatment and least potential for quality of life issues.

Your PSA, rectal exam, and biopsy report-You must know the specifics of your disease and the ramifications of each in your decision. Low PSA, low Gleason’s, normal rectal exam then you can go for the less aggressive therapies. If you PSA is high, your biopsy has high volume and high Gleason’s, then you have to be more aggressive in your treatment choices.

Bias- To thine own self be true. If you are biased toward or against surgery or radiation, this will heavily influence your decision. This is not right or wrong, just see it for what it is. Bias is not very scientific.

Cure is a priority-If cure is your primary factor then you will choose what you feel will give you the best chance of cure. You will value cure over potential for side effects or ease of treatment. Admiral Farragut-“Damn the torpedos. Full steam ahead.”

Risks are a priority-If you are this patient then you will make your choice by which potential complication worries you the most. Here you have to have a thorough and educated understanding of both the post-treatment issues of surgery and radiation. Hint-surgery is a pay me now risk, radiation is a pay me later risk.

Ease of treatment is a priority-This patient will choose by the “I want my cake and eat it too” method. The treatment that best blends risk with cure in their estimation. Again, this patient must see his choice for what it is-“I am choosing the treatment primarily because it will affect my life the least.”

What have you learned from family, friends, or the internet?-This is huge and a source of “bad information.” It’s Okay to do your research, but be careful. Run it through your caregiver. Remember the used car salesman analogy in” The Decision”, If you are betting on the used car salesman that does it every day or the guy buying a car once every five years,(who has found prices on the internet ) who do you think will win?

Misconceptions about prostate cancer-Yes most prostate cancers are slow growing. Yes most people die with prostate cancer instead of it. The fact remains that 30,000 men die a year in the U.S. of prostate cancer. If you are young and unfavorable parameters in your biopsy and PSA then making a decision based on the above misconceptions is a decision made in error. Everything has to be specific to you… don’t do what your friend or uncle Bob did because his prostate and his disease ain’t your disease.

A biopsy of the prostate involves obtaining a representative sampling of 12-16 small cores of tissue; however, it can give you a clue as to the nature of the cancer in the entire gland and help in your decision-making process. The two most important features of a path report showing prostate cancer are the grade, or Gleason’s score, and the number and percentage of positive cores, or volume of disease. The Gleason’s score is indicative of the potential aggressiveness of your cancer and is determined by a pathologist, who evaluates the two worst areas (highest grades) of your specimen and assigns each area a number between 1 and 5. The most common Gleason’s grade found in positive biopsies is 6, or a 3+3, which is referred to as moderate grade. A Gleason’s score of 7, which represents a 3+4, or above is considered high-grade prostate cancer. The score is important because the higher the grade, the more aggressive and unpredictable the cancer. In my opinion, a higher grade should make a patient lean toward a more aggressive treatment.

A biopsy of the prostate involves obtaining a representative sampling of 12-16 small cores of tissue; however, it can give you a clue as to the nature of the cancer in the entire gland and help in your decision-making process. The two most important features of a path report showing prostate cancer are the grade, or Gleason’s score, and the number and percentage of positive cores, or volume of disease. The Gleason’s score is indicative of the potential aggressiveness of your cancer and is determined by a pathologist, who evaluates the two worst areas (highest grades) of your specimen and assigns each area a number between 1 and 5. The most common Gleason’s grade found in positive biopsies is 6, or a 3+3, which is referred to as moderate grade. A Gleason’s score of 7, which represents a 3+4, or above is considered high-grade prostate cancer. The score is important because the higher the grade, the more aggressive and unpredictable the cancer. In my opinion, a higher grade should make a patient lean toward a more aggressive treatment.

Volume of disease, or percentage of the biopsy cores that contain cancer, particularly if present on both sides of the prostate, is also important as it may indicate the amount of disease in the entire gland. So, low grade and low volume are good things, and high grade and large volume are not as good. Knowing this helps you make a decision regarding your treatment. If you had a choice between having a low grade or low volume, low grade is much better. High grade (Gleason’s score 7 or greater) is unpredictable, more aggressive, and accounts for most of the deaths attributed to prostate cancer. If you have a high Gleason’s score, you may not have the same results as your friend who had a low Gleason’s score and did well with a particular treatment. If you are basing your decision on what he did without knowing the specifics of his biopsy, you are making a decision based on a flawed premise.

The chart that follows is a simplified overview of the various combinations of Gleason’s score and volume of disease seen in prostate biopsies. What I hope you will learn to do is to take each of the issues related to you and your cancer and, for each, evaluate which treatment is best suited to you. As it applies to Gleason’s score and volume of disease, use the chart below to determine which grid most applies to your biopsy report. If you fall into the favorable parameters group, low Gleason’s score and low volume of disease, and you want to purse a less aggressive treatment, it is reasonable to do so. However, if you are in the unfavorable parameters group, you may need to put aside your concerns about the ease of treatment or impact on your daily life in favor of choosing the more aggressive therapy with the most options for cure. (You can do radiation after surgery, but it is difficult to do surgery after radiation.)You need to know the parameters of your biopsy and the significance of each to help you in your decision. As you progress in your journey, you will begin to consider all the parameters, in addition to the specifics of your biopsy; which parameters you ultimately weigh most heavily in your decision can be determined only by you.

In addition to the biopsy specifics, the most important of which is the Gleason’s score and the number of cores positive, you need to be aware of your PSA and the findings of your rectal exam. (A palpable nodule implies capsular extension and this may impact your decision making process.)

You have had the biopsy and have been told you have prostate cancer. The problem with a decision about what to do is problematic because all of the treatments have side effects.

You have had the biopsy and have been told you have prostate cancer. The problem with a decision about what to do is problematic because all of the treatments have side effects.

The decision is the meshing of three major issues. The biopsy specifics, your “who are you” issues, and your assessment of risks vs. benefits as it pertains to you.

What follows is a breakdown of all of these issues and then culminating in the McHugh Decision Worksheet. To take the worksheet you will need to have evaluated all the issues to answer intelligently.

So….the process begins. It starts with an intensive evaluation by you, your family and loved ones. It ends with a “gut” feeling of what is right to do for you, for the right reasons with the full understanding of all of the treatment ramifications.

The biopsy specifics (your disease) and importance in your decision.

McHugh ” Who are you?” factors and the importance in your decision.

Excerpt from ” The Decision”

How I made my decision

When I began the process of determining which treatment option was best for me, I had not yet formulated the “who are you” concept. However, I used it intuitively as I had when working through the options over the years with patients of mine. My general health was good; all options were open to me. Cure, ease of treatment, and time out of work concerns were the most important factors to me and vied for the most prominent role in my decision. The risk of impotence and incontinence associated with surgical removal did not worry me as much as the complications and unknown future complications of radiation therapy. Having performed hundreds of prostatectomies over the years and knowing how my patients have done with surgery gave me some degree of confidence about my favorable chances of retaining continence and potency. I also had confidence in the treatments necessary for the correction of these issues if they were to occur. In my practice, the patients who did well with surgery usually did very well, without the unknowns and potential downside of radiation. The inability for those who chose radiation, and had problems, to do anything other than take medicines was a big factor in my decision. At the time of my diagnosis, I had some underlying early symptoms of an enlarged prostate, mild frequency and some decreased caliber of my urinary stream, and I knew that radiation would most probably worsen that. The fact that I was 52 played a role as well. I knew that my years at risk, figuring that I would most probably live into my 70s, would be over 20 years. This made me gravitate heavily toward what I felt was the most aggressive way to deal with the cancer. My path report was favorable in terms of Gleason’s score and volume, but my years at risk trumped this. The concern that cancer can return after radiation, not only because the cancer is outside the radiated field at the time of treatment, but because of the potential inability of radiation to kill the cancer, played a role here. Reoccurrence of prostate cancer after radiation, if it happens, usually happens five to eight years after treatment. The potential for inadequate placement with seeds heightened my concerns regarding my years at risk because those were probably longer than the average time to reoccurrence with radiation. In the end, my decision was driven by my belief that my best chance for cure was with surgery.

Summary of my decision – Now, you work through the “who are you?” factors the same way, as I did, for your situation.

How you should make yours – Now it’s your turn

Armed with the information in this book, you too can come to a decision about your cancer’s treatment that you will become comfortable with. Begin with your general health and slowly work through which concerns trump others, and you will begin to narrow it down. The main point I’d like to make here is not to let your decision be one-dimensional (based on what a friend did, a commercial you saw, or a brochure you got in the mail). Ease of treatment, i.e. radiation, is a major concern for some; I explored that path as well. However, if you choose radiation because you feel there are fewer side effects, a better cure rate, or you are experiencing obstructive voiding symptoms, then you may be making an error. Have your radiation therapist thoroughly explain the negatives of radiation and be sure you are comfortable with his answers. If you have immediately gravitated to surgical removal, your health is marginal, and you are in your 70s, again you may be making the wrong decision. My advice is to explore all you know about your disease, your “who are you” factors, and discuss this with your health care providers to arrive at your decision.

My advice? Order “The Decision” and Patrick Walsh’s Book, speak to people who have gone through the process (remembering to compare apples to apples and oranges to oranges), and use as your internet resource the Prostate Cancer Page on the Johns Hopkins website. On that site find the Partin table and plug in your stats. This table will tell you the chances of having capsular extension of your prostate cancer. This is an important pre-decision distinction. If you think you want to have surgery because “I want to be done with it” but the Partin table tells you that you have a 25% chance of the PSA rising after surgery and that you’ll need additional radiation…will that make a difference in your decision making process? It would for me.

Now with all of the “Who are you?” factors addressed and you have done your homework-you are ready to make a decision. This process will not prevent the chances of a bad result, complications or side effects of your chosen treatment but it will limit them.